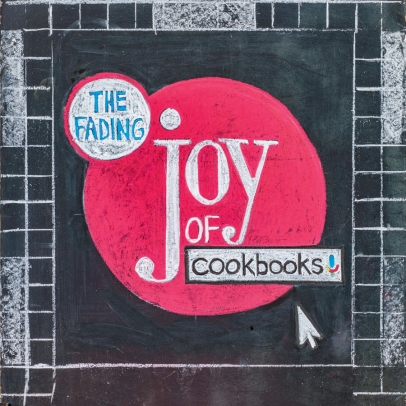

The Fading Joy of Cookbooks

Even in the internet age, cookbooks are tough to let go

Cuisine is not invariable … but one must guard against tampering with the essential bases.

—Fernand Point

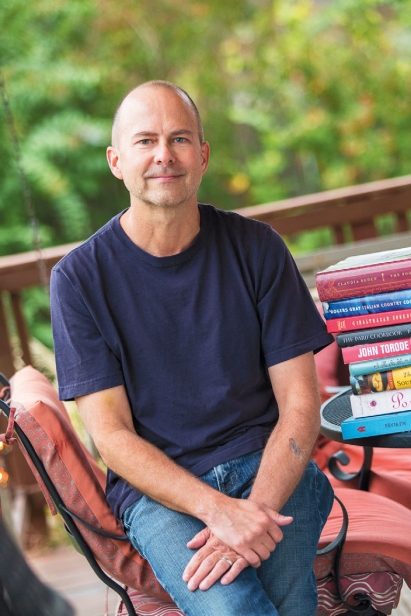

I looked up one day to find my cookbooks blown to the four corners: in the closet of my kids’ bedroom; in the library, with the book books; boxed, on the garage floor (there are more in the attic above it); and scattered throughout the living room wherever a free space announced itself. We’d done some kitchen remodeling and, while we were now swimming in cupboards, the shelf space had diminished. I took it as a sign, or at least an opportunity, that it was time to begin thinking about winnowing the collection.

For a lover of books and a curious cook, this is a teeth-pulling event, with all the blood and no fairy money under the pillow. An unlearned cook, I’d taken cover under them, soiled them, browsed them, often in my sleep, over what had become decades. They were like my children.

Cookery books, the English call them, and my English landlord in France presented me one—Auguste Escoffier’s 2000 Favourite French Recipes—that I wish I’d brought home. We lived in southern France, on goat cheese, olives and co-op wine, and Escoffier was all Parisian pomp, but it would at least put two classic French books in my collection.*

A romantic at heart (and certainly head), I didn’t learn to cook in order to feed my family or save money. I learned to cook because it helped me imagine places like Provence, Galicia and Emilia- Romagna, all from my galley kitchen. When I finally did shop and eat my way through some of Europe, it felt like a bookend.

What the cooking shows started, the Internet finished off: For some, it’s more fun watching somebody else do the cooking. I like cookbooks because I like books, and I keep them for much the same reason: because I enjoy cracking spines. But anymore, the urge to Google is too great, and too rewarding, at least in the discovery sense. And so the cookbooks, each with its theme and finite recipes, become antiquated.

But, oh, which to toss and which to keep? They’re all passengers on a sinking ship, all beloved and momentarily sweet on one another, united in a common cause. The only reason to keep them, beyond a love of books, is their novelty—a tenuous reason indeed. But to have to grab-bag their digital equivalents across the various cubby holes of the Internet would be tedious, even if possible. What to keep, for me, becomes not only a question of space and utility, but of legacy and intrinsic value, the curation of my cooking life, in a nut. If I am to make choices—and I must, as much as I have to decide which favorite coffee mugs and handed-down crockery stay and which go—it usually comes down to sentiment, and that’s always a hopeless case.

Edward Behr did his culling in a 2008 edition of his exquisite quarterly, reducing his lot to nine volumes, all of them French and Italian classics. “These are books of traditional food,” Behr wrote in his apology. “Some of the writer-cooks only present what they saw and knew, not questioning or refining as far as I can tell. That’s fine; I can ask my own questions.”

Cookbooks as maps chart courses by which to navigate a path toward—what? Buried treasure? Great unknown? A lifetime of adventure? Maybe something as big as enlightenment? “Turning the book’s pages,” Behr wrote of Elizabeth David’s French Provincial Cooking (1960), “I’m reminded of the many things I’ve never made and always wanted to. I see other items that I didn’t know existed, and I feel I always wanted to make them, too.”

I don’t know if I could trim mine to nine, but if I had to keep only one, it’d be The Balthazar Cookbook (Clarkson Potter, 2003), from the SoHo brasserie. It’s the most beautiful in my collection, of any book. I have been careful not to cook with it on the counter, lest it spoil. Photographed by the great Christopher Hirsheimer, it makes me cook things I used to leave to the pros, and it has the best backcover blurb of all time, from Bono: “I went for breakfast; I stayed till supper.”

Marylène Altieri, curator of books and printed materials in the Schlesinger Library at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, does not feel my pain.

“Although many people make use of online resources today, people are still buying and cherishing printed cookbooks,” she said, “as I can tell from the volume of dealer catalogs and gift offers from individual collectors that we receive all the time.”

The Schlesinger houses a 20,000-and-growing body of current and historic cookbooks and collections, among them Julia Child’s 5,000 volumes. It’s hard for me to imagine a woman of Child’s exuberance cramming all of that happily onto an iPad. Nor should I expect a curator of “books and printed materials” to predict a paperless era. “Publishers will continue to find ways to make the cookbook desirable and to find new producers and audiences for them,” Altieri said. “Food blogs and databases of recipes will find many eager users, but there will still be a need and desire for printed cookbooks. “I think the Internet will be an adjunct to the world of cookbooks but will never replace it.”

*Paula Wolfert’s The Cooking of Southwest France is the other, but it’s too authentic to be much good—to me, anyway. Like her recipe for Cassoulet de Toulouse, which requires five pounds of pork, six duck legs, and three days to prepare. If you can’t imagine eating such a dish, imagine cooking it.