Stainless

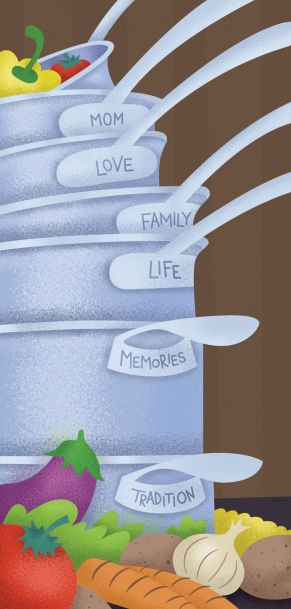

Mark Brown learns that good cookware will outlast most of life’s trials and errors.

Most guys never forget their first car, and nor do I—an Avon-green Buick that my dad bought off my grandfather when both were about to roll odometers. Unlike most guys, I didn’t worship it that first car, didn’t even say grace over it. That I reserved for my first set of stainless-steel cookware.

My mother bought it for me in a mall department store, a couple of days shy of my 29th birthday. A month earlier, she’d given me for Christmas the Great Chefs cookbooks from the Discovery Channel series, which I watched religiously in the middle of the day when I should have been looking for a job.

With a new set of cookware, I thumbed the books for easier pickings and began proving, dish by dish, the elusiveness of great.

These were the Teflon days, when only restaurants and doctors sweated vegetables on copper or stainless. If you found them, it was usually in some pricy shop for hobbyists, where they hung from racks like game birds getting ripe. There or at the mall, where you found everything else. My mother, the cook in my life, drove us.

We passed through showrooms of blue jeans and bedframes, everything shining passively under the high beam of fluorescence. We found the modest kitchen section, its mixers standing sentry, its wedding registry gleaming bone-white and pastoral. She spotted and we agreed upon the most reasonable choice: a heavy-bottomed, five-piece set—not All-Clad, but not bad.

“Miss?” she said, attempting to flag a clerk who floated by on a pair of orthopedic Mary Janes and a cloud of ennui. After failing to gain her attention, my mother swiftly cut a wake to the service department. There, she informed the resident Barney Fife that it was her plan to purchase a set of stainless-steel cookware, if that would be all right with everybody. He came out from behind his Formica counter to ring the deal himself. My mother glowered and paid in cash.

When I got back to my apartment and opened the boxes, I handled the steel to get a feel for it, like some Excalibur I’d just unearthed. I was Arthur, the boy king, girding up for the round table.

Before I turned 30, I managed to burn the medium saucepan, steaming some new potatoes. I was cooking dinner for my recently ex-girlfriend, in the townhouse we’d shared for several months. When I moved out, I left the stainless behind for some complicated reason. We did a lot of cooking in our brief time, and the cookware—its hollow, heat-resistant handles, its still-shiny radiance, the weight of it—served as a bridge of some sort.

We sat in the front room waiting for water to come to a boil. We sipped wine in relative silence, listening to Britpop. When we spoke, it was with the clumsiness of a hastily brought-together sauce Bearnaise. She turned toward the light and for the first time I saw the marks on her neck: soft blue blossoms sprouting just above the clavicle.

“Who did that?” I asked, sounding as stupid as any other wounded boy cooking dinner for his ex. She looked at me with a sadness that I sometimes get buying winter tomatoes. I shut my mouth and fell into the bottomless depths of my wineglass.

Something was on fire and it wasn’t hearts. It was also too acrid to have been the chicken roasting in the oven. By the time we found it, the water had long boiled off and the inside bottom of the pan now burnished a bruise black, a shade or two above the eggplant that we’d painted the walls in the fall before. In the bottom of the pan, the potatoes had cracked and their skins shriveled.

“I’m sorry,” she said, looking at the fresh stain on the pan. I just sighed and took another sip of wine. A decade and half later, I finally tossed the pan when the bottom plate peeled away. Foolishly, I kept the steamer insert around for a while, thinking it might come in handy for something and, anyway, it at least was unblemished.

I stopped steaming vegetables after that and began sweating them instead. Thus did the sauté pan become my shining sword. I began with aromatics and then stretched my wings. In this pan, I learned the patience of cooking protein in fat, the acidic science of deglazing, and the patience of reduction. But I was a test kitchen without a guinea pig. At 10 inches wide, the pan was built for two.

The first date with my would-be wife could hardly be called that. She drove me home from a party and we talked in her car for easily an hour. Across the street from my apartment, in the basement of the Convention Center, circus elephants roared a civic chorus. I tucked a kiss in under her ear and walked the four floors up in a cloud.

On the second date, I took her to Tucci’s, or she took me. On the third, I cooked. With breezes blowing through my apartment windows, I put on John Coltrane and began to prep. On the menu: a salmon dish from my Union Square Café book, garnished with corn and shiitakes, brightened with a bit of fresh basil and napped in a balsamic-butter sauce. She ate it with discipline and reverence, as if her afterlife depended on it.

We drank a Chardonnay and sat on the balcony, tossing words on summer winds.

Three years later, she married me and learned what I already knew—that the eight-quart stockpot was the utility infielder of my kitchen lineup. In ours, old dishes were retired and new ones trotted out. I tried my indulgent chicken etouffee on her once before giving up, to both our liking. (I brought it back out a decade later for our two sons, and for old time’s sake. “What’s wrong with this chicken?” the younger of them asked.)

In its place, I began perfecting a leaner Alsatian dish in which prunes, bacon and fingerling potatoes softened against the sautéed chicken. A gentle braise in stock and thyme leaves and even the pot appeared to breathe easier.

I’m beginning to detect a breach in the core of the small, two-quart saucepan, the little pan that could. It’s gone through nothing too stressful in its relatively brief life, I mean, other than having its face licked by several thousand BTUs every day. Anyway, as if on cue, my mother has been spotting me pieces of her All-Clad, stuff she picked up on sale, or in odd lots. Still in their boxes, I accept them bittersweetly, defiant and flustered at the downsizing of her kitchen.

I’ve lately inherited another thing from her: Thanksgiving. It takes all pots on hand to assemble the medley of dishes that look only a little like the ones she’d settled on over the seasons. It’s a tall order. I try to limit the starches, season and moisten the meat and elevate the greens from the status of also-ran, to mixed reviews.

It doesn’t help that I hated cooking the same thing twice.

Mark Brown is the author of My Mother is a Chicken (This Land Press, 2012).