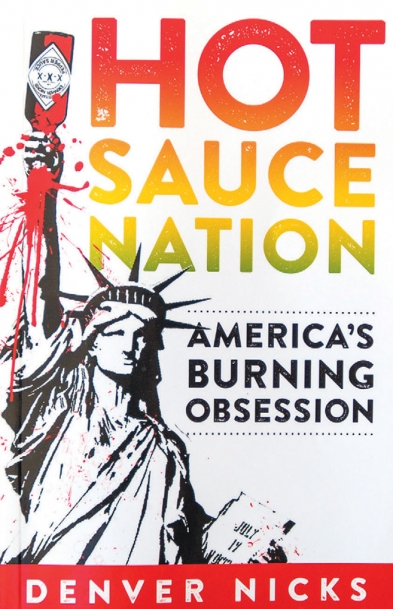

Hot Sauce Nation

Denver Nicks, a Tulsa native, is a journalist, writer, producer and a regular contributor to TIME. He is the author of Private: Bradley Manning, WikiLeaks and the Biggest Exposure of Official Secrets in American History. His second book, Hot Sauce Nation, was just released.

EDIBLE TULSA: Tell us about your Tulsa roots.

DENVER NICKS: I spent the first 20 years of my life in Tulsa, in the Riverview neighborhood just south of downtown. I went to Eisenhower, which is the best gift my parents ever gave me because being able to speak Spanish has changed my life over and over again, then Carver then Booker T. Go Hornets! I moved away for college but I’ve lived in Tulsa on and off since then and I go home all the time, so I’m still very much connected to the city. Tulsa got a hell of a lot cooler right after I left. I’m not sure what that says about me … but anyway.

ET: It seems as though the character Two Shack was the core foundation for this book many years ago. What was it like to share this experience?

DN: Two Shack is a force of nature, a subtle maniac, a dreamer, a pragmatist, a benevolent genius. Growing up with him—he’s my dad, of course—was pretty rad, because he included me in many of his adventures and always encouraged adventures of my own. At heart, Hot Sauce Nation is about the beauty of multiculturalism and finding meaning and strength in hardship, which are all things that Two Shack helped shape in my character as I was growing up.

ET: If you had to name a Hot Sauce Capital for this nation, what might it be?

DN: This may be controversial, especially to anyone from New Mexico, but I’d have to say New Orleans. The history of hot sauce in America is intimately intertwined with the history of slavery and of the black experience in this country, both of which are huge parts of the history and culture of New Orleans. Also, Louisiana still employs more people in the hot sauce industry than anywhere else and Tabasco is made near New Orleans and Crystal is made in New Orleans and that’s just scratching the surface. Yeah, actually there’s no contest. New Orleans, definitely.

ET: What town or region had the most hot sauce shops?

DN: Hot sauce shops tend to corner the market wherever they are so you don’t usually find a whole lot of them in the same place. There are actually two in the French Quarter now, which lends support to my previous answer, but most cities will have just one real proper hot sauce shop.

ET: So much of this fascinating book revolves around pain. What’s the most convincing argument you heard as to why one should feel the burn?

DN: There’s the fact that it leads to a flood of pleasant and painkilling brain chemicals, which is nice, but my favorite argument in favor of the burn is Nietzsche’s, which says that pain and pleasure are inextricably linked and that achieving greatness and living life to the fullest necessarily means enduring pain, and that we should therefore heartily embrace pain—or, as Nietzsche puts it, “live dangerously! Build your cities on the slopes of Vesuvius!” I love that.

ET: A book on national security, then hot sauce, what’s next for you?

DN: Right now I’m working on a book about a famous murder and police brutality trial that happened in Oklahoma in the 1940s. In keeping with Hot Sauce Nation, I’m also starting a project that looks at multiculturalism in Europe and all the many wonderful things immigrants have contributed to cultures across the pond over the years.

This Is What It’s Like to Overdose on Hot Sauce

There’s an episode of “The Simpsons” famous among chiliheads in which Homer eats several of the “Merciless Peppers of Quetzlzacatenango, grown,” Chief Wiggum tells us, “deep in the jungle primeval by the inmates of a Guatemalan insane asylum.” Homer goes on an immersive hallucinogenic trip, complete with Johnny Cash as the voice of a talking coyote, which launches him on a journey to find his soul mate.

I’ve had as many hot sauce overdoses as any garden-variety chilihead, but I’ve never had a full-on psychedelic experience induced by chilies. One hot-sauce overdose in particular, however, did reveal to me the power of the flood of brain chemicals triggered by a heavy dose of hot sauce.

At the NYC Hot Sauce Expo in 2015, I took a chili challenge at the Voodoo Chile booth. In order to hop on what Voodoo Chile’s president and “Chief Sauceologist” Thomas Toth calls the “Endorphin Express,” I had to tangle with his Scorpion Pepper tincture, which weighs in at a daunting 3,278,000 Scoville Heat Units (SHU). For comparison, that’s roughly 18 times hotter than Dave’s Insanity Sauce, 650 times hotter than Tabasco, 1,300 times hotter than Huy Fong Foods’ Sriracha, and about twice as hot as the hottest chili pepper known to humankind, a cultivar of Capsicum chinense known to the world as the Carolina Reaper. It was not a pleasant experience—at first.

I was made to eat one small dollop and stand with Toth at his booth without spitting or ingesting anything else—so, no milk, no beer, not even water. After two minutes, I had a 30-second window in which to bail or to go all in and eat another dollop for another two-minute stretch.

Under those conditions there is no effective cooling method available except for the devil’s bargain of forming your mouth into the whistling shape and inhaling sharply; a devil’s bargain because the breath somehow seems to burn even worse on its way out. One has only to stand and be with the pain. The key is to remind yourself that the whole thing is a trick of the mind. Toth’s Scorpion Pepper tincture burned worse than anything I tasted before or since, like 3.278 million tiny ember-hot knives dancing around my mouth, but relief of a metaphysical sort came by simply reminding myself that the hot knives were an illusion. There was no real damage being done. Practitioners of mindfulness-based stress reduction use meditation techniques to achieve a similar effect to help people suffering from chronic pain. The idea is to help them identify and isolate their pain and ultimately decouple it from other sources of suffering that physical pain can evoke, like fear and hopelessness.

There’s a Zen-like pleasure in this part of the experience, in which the overwhelming pain takes hold of your complete attention and reins in your focus to the immediate experience of now, allowing a sense of presence and a kind of meditative peace to arise within.

Once the allotted time had passed, I chugged a beer and speed-walked toward the bathroom, doubling over for a moment as the stuff hit my stomach and my gut flinched into a smoldering knot. When I reached the sink, I opened a faucet of cold water and put my mouth under it for two minutes or so. Then I made a beeline for the ice cream stand, cut to the front of the hot sauce ice cream line making hand signals to indicate my predicament to a sympathetic crowd—this was a hot sauce festival after all—and sucked down an entire pint of Bonfatto’s Spice Cream’s Whodathunkit?! Sweet Peachy Heat Wave.

For hours after the pain subsided, I felt simply marvelous, like a creature made of clouds and light—clear, pleasant, calm and energetic, but not anxious. This was my brain under the influence. I was high as a kite on hot sauce.

Adapted from Hot Sauce Nation: America’s Burning Obsession, copyright c 2016 by Denver Nicks. First edition published Oct. 1, 2016, by Chicago Review Press. All rights reserved.