Tuck Curren

Consumed With Cuisine

Restaurant impresario Tuck Curren is a mama’s boy. “Mom, always Mom. It was food all the time. In New York, she regularly went to the butcher for the Sunday roast, and we always enjoyed food around the family table,” Curren acknowledged. He laughed as he remembered that, in California, “If she weren’t home at dinnertime, we kids cooked. We just liked to eat.”

These days Tuck’s mom, Boz, is around for most family meals. The active and agile 85-year-old moved in with her son and his wife, Kate, seven months ago, but they don’t ask her to cook. Kate does all the home cooking. Plus, the food styles in the Currens’ home kitchen are different than his mother’s. These days, the emphasis is on spicy, global fare: Turkish, Croatian or Filipino—anything that has some zest to it and is fun to cook.

“Mom makes the greatest lasagna, the greatest cheesecake, sauerbraten. She jumps at the chance to show her chops,” Curren continued. “Sometimes we just tell her, ‘Go ahead, Mom.’”

Curren, 64, has also taken calculated risks in the Tulsa restaurant scene for three decades. Perhaps his history of swimming competition gives him the confidence to take chances on new ventures. Maybe he still hears the coach’s whistle, the starter’s pistol, when he dives into new culinary adventures.

On a sunny day in California, as Pacific waves crashed on a nearby beach, a teenaged Tuck Curren gasped for air, his arms aching from exertion. During the brief rest between repeat intervals, he looked across the lanes of the Santa Clara Swim Club pool; a slightly older teammate, Mark Spitz, the future Olympic role model, looked back. Undaunted, Curren readied himself for the sound of the whistle, for the next burst down the pool.

So that Tuck, 14, could compete with the best swim team in the world, his father—who owned a Lincoln-Mercury car dealership in posh Westchester, New York (“We were ritzier back then,” Curren recalled)—headed to Santa Clara, California, with his wife and their four athletic kids.

Tuck, the eldest sibling, had the confidence to push himself, to push back against the weight of a challenge; a certain maturity that would be tested rigorously when his dad passed away one year after the move, and when he switched to water polo, earning a full-ride scholarship to San Jose State University.

After college, Tuck came to Tulsa to visit a brother and stayed. Queens borough—born Kate Foley came to Tulsa from Los Angeles for a management job with the Interurban Restaurant. They met in 1983 when he was a bartender at the former Interurban South, and the pair have been inseparable ever since. The two former New Yorkers married in 1985.

A year after their nuptials, Curren became a server at Bob and Mary Faulkner’s Bodean Seafood Restaurant on the northeast side of 51st and Harvard. He was joined by a fellow East Coast emigrant, Jersey boy and future Tulsa culinary icon, Chef Michael Fusco, whose first professional gig after Johnson & Wales culinary school was Bodean.

Even in his absence, Bob Faulkner’s advice is always in Curren’s ear: “Don’t get too top heavy in management costs [staff]; you can’t get rid of it.” And he kept developing his kitchen skills.

The newlyweds used their cooking fascination to scour food magazines and cook up eclectic regional cuisines, frequently preparing a Sunday meal for the bachelor Fusco. “From soup-to-nuts, we made every course,” Curren said. “That’s how we really learned to cook: cooking for family and friends, trying unfamiliar ingredients, staying on the cutting edge of cuisine.”

For 33 years, Tuck and Kate have always worked and cooked together. Always.

Partnering with Mary and Taurus Faulkner in 2000, they opened Biga (named after the term for Italian bread starter) and T2 (American cuisine) restaurants as bookends of a new strip center at 43rd and Peoria. Business flourished, and the venture looked smart.

After 9/11/2001, businesses in the United States pulled in. Used to a steady diet of corporate dinners that added significantly to his restaurants’ bottom lines, T2 suffered a soon-to-be-fatal blow. As a cost-saving measure, Tuck became the executive chef, cooking on the line. Financial pressures continued and T2 closed.

On a snowy evening a year or so later, the doctor-owner of the center shook off the cold at Biga with a glass of wine. He suggested opening another restaurant in the old T2 location. Curren smiled as he recalled, “I told him ‘I just closed one there!’” The couple’s first reaction was no, but they knew they wanted another restaurant, and the doctor was willing to finance the buildout. Local Table— utilizing local products—became a reality.

Curren’s understanding of the multi-level value of growing produce spawned a new project: a community garden. Farmed by Juvenile Detention Center kids, Local Table bought the produce for a decade.

During the heyday of Local Table, the California food truck movement reached Tulsa. Curren sensed this was more than a fad and created the Local Table food truck, which continues today.

When asked if he would ever stop his entrepreneurial bent, Curren’s eyes lit up as he laughed, “No.” No surprise, then, the Currens have a new venture.

George Kaiser and others are developing a “go-to” district, the Brady District, filled with restaurants, boutique hotels, bars, music venues and world-class museums. When the Kaiser Foundation contacted Tuck with an idea for a restaurant—jazz club, Tuck made a Day 1 decision to jump at the opportunity and a Day 2 decision to figure out details for “the best opportunity” he has ever had: a symbiotic combination of a creative restaurant and a bluesy jazz club, together called Duet.

Kate and Tuck are completing construction of Duet in a Kaiser building renovation at Archer and Detroit, just north of the Magic Book Store in the Brady District. The new business features a choice of an elevator or steps that lead down to the jazz club— already booking national acts—a large patio and an open-view kitchen. It is a new concept, combining a restaurant and music venue on different levels.

The food will be a blending of different ethnicities with American cuisine to form their own “duet.” The completion date of spring 2018 is at hand. Regardless of business demands, one tradition never suffers: the family’s Sunday-afternoon meal.

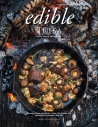

A recent Sunday soiree held during the Winter Olympics naturally demanded the cuisine of Korea. A writer and photographer entered the Curren household, filled with peppery aromas and the sounds of happy people. Grandson Vincent, 2, did his best with an apple in the kitchen; 5-year-old Hank held court with attentive older relatives in the living room. Kate minded ginger-pork dumplings in a silver-metal Asian steamer, finishing the Korean chili paste sauce for the chicken wings that would receive a garnish of sesame seeds.

Tuck placed the wings and dumplings on the living room table, as fun-loving son Zack, white flour decorating the tops of his shoes, entered the melee, fresh from baking bread for his restaurant, Trenchers Delicatessen. The party had officially begun. Posing for a kitchen photo, Tuck pointed to Zack’s Four Roses (bourbon) hat, joking, “That’s what we raised our kids on!”

On the counter, a tall glass jar of fermenting kimchi worked its magic. A neighboring bowl of quick-kimchi cucumber slices was moved to the dining table. Kate bustled purposefully, plating gorgeous food on platters, adding fragrant sauces, smiling at the familial conversations percolating around her.