Chef Curt Herrmann: A Serious Focus on Cuisine

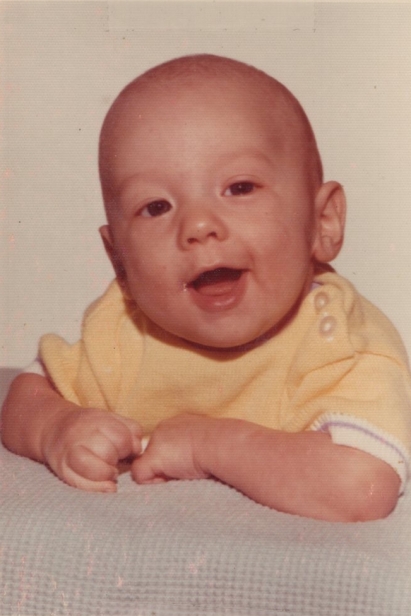

Grandfather Joe picked up 5-year-old Curt from kindergarten on the south side of Chicago. For the first four years of grade school, the Lithuanian-born grandparent babysat the youngster. Taking him to his butcher shop, Jowaze (joe-WAZ-ee) Herrmann placed Curt on a crate in the corner, next to the cutting table. The always-cold basement room held three other meat cutters: two Old-World Germans and an eastern European. Thick native accents ricocheted off the moist stone walls. Young Curt Herrmann, the future world-class chef, soaked it in.

The men in the dark room butchered fresh meat brought up from the crypt-like room below. Joe handed a sausage snack to Curt, who sat patiently, watching the dance he didn’t understand, listening to the foreign dialects of the giants surrounding him. Called “Joe the butcher” by the neighborhood regulars, Grandfather prepared all the meats for their old-school weddings and family celebrations. Broken-English patrons entered his shop, knowing that Joe always had their specified favorites on the ready. He brought various cuts of meats to Curt’s house that his mother, Patricia, turned into traditional, ethnic foods.

“She cooked Polish, Lithuanian, a lot of stews,” recalled Curt. She often grilled the protein gifts from Joe’s pantry. Early on, Curt’s job was sink duty. Yet, by fourth grade, he was more interested in the cooking process than scrubbing pots and keeping the kitchen tidy. Sometimes, his grandmother helped maintain their clean and organized household.

Grandmother Herrmann helped in the butcher shop, and often the matriarch showed up at her son’s house to scrub the floors, clean the windows, reminding Curt that in the old country, people helped each other. “She’d tell us, kids ‘Don’t step on the floors, go outside,’” he reminisced. Outside was the large family garden with its corn, tomatoes, cucumbers, squash, some herbs and lots of beans, creating an early exposure to the beauty of land-to-table. And his mother exposed him to the entrepreneurial spirit when she took her passion for food to the open market.

She always wanted a restaurant. Curt’s father, Joseph Augustauv Herrmann, an electrical and plumbing engineer by day, helped fund her vision. With a 12-year-old Curt, older brother Carl and younger sister Beth watching, the couple opened an American-style restaurant called the Port of Call—steaks and lobster—in 1984 on the St. Lawrence River in Kankakee, outside of Chicago.. Curt became a dishwasher and prep cook at $2 an hour. They hired a “dirty Frenchman,” Oscar Papineau, to serve 100 patrons, which diminished by half during the winter when the patio closed. For those Port years, the Frenchie was a good fit.

Tragically, Patricia was diagnosed with cancer and was unable to continue the rigors of the restaurant business. The Port of Call closed in 1987 and Papineau focused on his full-service butcher business, Oscar’s Meats, which operated in one of his barns. As the gentleman grew older, 15-year-old Curt and his older brother, Carl, visited him to help break down a deer, sip some Southern Comfort and Jack Daniel’s—it was cold up there in the winter—and crash at the farmhouse. Communing with the aging Frenchman was not Curt’s only cold-weather activity.

An enterprising Curt ran trap lines in the fall and winter months. Trapping raccoon, mink, coyote, fox and other furry quadrupeds and selling their pelts provided enough funds to buy his first vehicle. Requiring transportation to his traps, school and a new restaurant job, Curt and his dad headed for the Chevy dealership, where the budding entrepreneur paid for a new S-10 truck.

**

Curt took up with a small, not-too-fancy restaurant in the Grant Park area for $2.89 an hour. His hours were restricted due to his age, and he wasn’t allowed to touch the mixer or slicer. “B.S.,” Curt offered from a recliner years later. “I already knew how to run all the equipment.”

The Dutch owner—kind of a holy roller with a strange sense of humor—quickly increased Curt’s duties to 55–60 hours a week; the youngster never turned down the extra work or complained. His mom did plenty of that, advising Curt to “Slow it down a little bit. What about your schoolwork?” Eh. He had a plan: cooking.

As always, Patricia supported Curt’s career path and referred him to an acquaintance at the Sheraton Hotel in Chicago, who could provide a good opportunity to elevate his knowledge, while working a more agreeable schedule. It was about 45 minutes away, but he had a new truck, so “no problem.”

Stepping into that arena, Curt’s eyes got big. This was a long way from the scale of a small, suburb diner. They did a lot of banquets, while pushing out some fine dining. George Limper, the executive chef, took Curt under his wing. Limper made some “serious” food and the quality of the kitchen staff inspired young Curt. The wanna-be chef did not mind the long hours that, habitually, made it more convenient to spend the night in the hotel. Calling his mom at 10:30–11 at night, Curt explained he would just stay at the hotel. Driving a long-distance home after another late shift, getting up after a short sleep, then driving to school became nonsensical. His hotel overnights became a two-year reality. Knowing their son was not the kind to get into trouble and that he was responsible, his parents decided, “Hey, let the kid do what he wants. He’s focused.”

And Curt had an employer and a teacher that figured into his personal development.

The Sheraton’s executive sous chef, Barry Fidlow, pushed Curt, who started his long stint at the Sheraton prepping vegetables, many cases a day. Fidlow planted the bug to go to the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in Hyde Park, New York), saying, “We’re going to get you there.” During Curt’s two-and-a-half years in Fidlow’s kitchen, his mentor hammered the notion that the talented adolescent attend the Hyde Park institution.

This environment of dedicated, talented people reinforced Curt’s passion for the food industry. His now-colleagues were motivated; it matched his drive to challenge himself to learn and excel. It reinforced his parents’ imprint of a sound work ethic. His chef-mentor’s caring core reached his soul. And there was a teacher, who also influenced him.

Curt loved the technical side of his high school campus. The wood shop, his favorite, provided a unique learning opportunity. Jerry Abbot, the observant instructor of the wood class, recognized the youngster’s penchant for hard work and his inquisitive nature. “Hey, Herrmann, you wanna work with me on a big project?” Abbot asked.

He pulled out some store-bought plans for Adirondack chairs. A couple of weeks later, half of a semi-load of cypress wood showed up at the shop’s backdoor. “Man, Mr. Abbot, that’s a lot of wood,” Curt exclaimed. “Guess we are going to make a lot of chairs.” Abbot directed Curt to trace out all the chair parts on the wood and distribute to others in the class.

Over the next two months, shop students fabricated the parts for the classic outdoor chairs; foot stools, too. Teachers snatched up their inventory at 30 bucks or so. If they wanted them stained or painted, no problem. As the word spread, community folks placed orders.

Curt lauded the process. It taught him organizational and people-management skills, taught him how to think, gave him integrity. Abbot—which means “father,” an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery—led his devout Catholic protégé through a pivotal period in the young man’s life. Armed with a variety of life experiences and a diverse résumé for a person his age, he was ready to take a big step.

Chef Fidlow helped with the CIA application paperwork and provided the required letter of recommendation from an alum. While still in his senior year and six months before the start of college classes, Curt and his mother had lunch at Chicago’s Four Seasons with several CIA representatives. They informed the applicant that they required an additional course, which was offered at a local community college. Curt thought to himself, “This is going to interfere with my [cooking] lifestyle. No big deal.”

Two days a week from 4 to 6pm, Curt diligently attended class. His Sheraton employers gladly endorsed his effort to comply with the school’s wishes. The required course completion document arrived at CIA before his 1989 high school commencement and he was set for the journey to Hyde Park.

**

Curt drove through the rolling hills, past towering trees near the campus, situated near the historic Hudson River. It was a postcard moment for the pickup driver from the Midwest. His first glimpse of the four-story, red brick Roth Hall with its six monolithic columns was inspiring. The architecturally resplendent structure, a former monastery, dominated the quaint campus. The Culinary Institute of America is regarded as the “Harvard” of culinary schools, a higher-education organization that prepares 1,200 gastronomes for the finest restaurants in the world. During the next 21 months, the rigorous training stimulated and stretched Curt’s imagination.

Typical of his take-no-prisoners work ethic, Curt dug in. His class was divided into four sections: two in the morning and two in the afternoon, each consisting of 15–17 students. Yet every person felt as if they were members of the same team. It was a close-knit family. He made some lifelong friends—one, in particular. Curt started in a morning section, Brooklynite Marj Alexander was in an afternoon group.

Although relegated to different sections, Curt and Marj knew each other. She was a charismatic, big-city girl and he was more Midwest-reserved. Thanks to Grandfather Joe, Curt was a natural fit with the meat fabrication instructors—making sausage and processing meat. “Curt was very dedicated to his culinary education,” Marj recalled, “which resulted in the class voting him Most Likely to Succeed.” And his talents landed him on the hot seat to serve a culinary icon.

Curt was assigned to be the personal chef for the French legend Paul Bocuse, who was one of the pioneers of nouvelle cuisine—less opulent than traditional cuisine classique and emphasizing the highest-quality fresh ingredients. He is the recipient of France’s highest honor, the medal of Commandeur de la Légion d’honneur. During his two-day Hyde Park visit, Bocuse designed his menu for breakfast, lunch and dinner. While Curt worked on those requests, Bocuse circled the kitchen stations.

All the CIA big shots gathered around the table for the cuisine prepared by the upstart from the Windy City. Among other foods, Bocuse wanted two poached eggs, profiteroles stuffed with foie gras, and Champagne. Curt remembers the decorated French chef as a “nice guy.” After surviving the experience, he returned to Garde class and the remainder of his training.

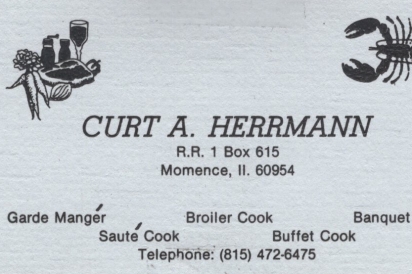

“That lasted until it was over,” joked Curt, who graduated with honors. “Then there was the externship at the Worthington Hotel, Fort Worth (owned by the Bass shoe people) for 4½ months, where money was no object for the kitchen.” He headed for his first professional cooking job at the Broadmoor in Colorado Springs, which Curt tolerated for a year.

His former boss Chef George Limper was living in Scottsdale, Arizona. Curt headed there, working in Limper’s restaurant, before taking a sous chef position at La Ventana in the prestigious Princess Hotel. After her externship in Miami, Florida, coincidentally, Marj was cooking for the Princess at their high-end, five-star, Catalonia-oriented restaurant, Marquesa. A new friend for the CIA pair was the sommelier for Marquesa, Tom Ratliff, a Tulsan. They formed a compatible trio.

Out of the blue, Marj approached Curt in a hotel hallway for quick question. “Want to move to Tulsa?” “Sure, why not,” Curt chimed.

**

Ratliff was the brother-in-law of Tulsa oil man David Sheehan and he convinced the businessman to hire the well-qualified chefs. Sight unseen, Sheehan hired Marj as a sous chef and Curt as chef du cuisine for Montrachet, his successful restaurant in the Brookside district, a trendy, older section of Tulsa. Ratliff became the sommelier.

The gypsy-like Brooklyn and Chicago cooks headed for the green country region of the Southern Plains to take over the reins of a restaurant with a bent for Southwest cuisine, inspired by the famous Dallas chef Dean Fearing. Marj and Curt brought in some “big city” specialty foodstuffs, like foie gras, caviar and truffles. Montrachet developed more of a French, classical menu and Tulsans flocked to it.

They ran Montrachet for the last couple years of its existence, 1995–97. What they spent on product was only marginally important to Sheehan, allowing food quality to match the chefs’ ambitious menus. The duo worked 17-hour days, scoured purveyor’s pantries worldwide and became the cuisine rock stars of Tulsa.

A thought occurred to Curt and Marj: “Why not do this for ourselves?”

Curt & Marj’s opened in Brookside in February 1997. Equipped with excellent (if secondhand) kitchen necessities, their eponymous venture targeted an untested market strategy: gourmet take-out foods, ready for the table. Rotisserie duck and chicken, soups, prepared salads and some Jewish foods—pastrami, corned beef, tongue, smoked meats and whitefish directly from New York - filled their glass deli case.

East Coast expats streamed to the store for knishes and other childhood favorites. Several linoleum-topped tables sat near the small service counter. Huge windows surrounded the front of their space, allowing full exposure to passersby. A screen door opened from the kitchen to the parking lot; smells du jour wafted through the mesh, like the beckoning strains of a pied piper.

The success of the venture added new pleasures to the awakening “foodie” culture. A second glass display case was added. White tablecloths covered an increasing number of tables, as adult beverages were added to the menu. It was Tulsa’s culinary hot spot. They were making a nice living. They knew everyone interested in good food and the gourmands knew them.

One of their aficionados was Barbara Hanford. Barb approached Curt while he stood at the front counter, asking him, “Hey, you want to work in Spain for about eight months?” She filled in some of the details: the setting, the farm, cooking for a family—Joanne Castro Hearst, actually. The name meant nothing to Curt. “Sounds good. Let me ask the boss. Get back to me,” he responded.

In the kitchen, Curt approached Marj:

Curt: Hey, Barbara just asked me if I wanted to cook in Spain for eight months.

Marj: Eight months, eh? That’s good for you. You’re young.

Curt: Sometimes, I don’t feel like it.

Marj: Who would you work for? What’s the name of the restaurant?

Curt: Some lady named Hearst.

Marj looked incredulously at her chef partner, “Hearst? Do you know who that is?”

Marj encouraged Curt, who called Barb—as it turns out, the director of all the Hearst properties—“Yeah, I’m in.”

There was no interview. But there was something else.

It was about Easter time. Barb came into the shop, asking Curt to make something special for an Easter Sunday gathering. She needed 12 naturally colored eggs (created with vegetable extractions) arranged into a little egg garden, plus a roast chicken and a lemon meringue pie. He arrived at Joanne Hearst’s Tulsa home at 31st and Utica on Sunday at the appointed hour of 7 o’clock. Curt wiped his feet, as he entered the museum-like house.

He crisped the chicken in the well-appointed kitchen. It had to be just right. Joanne enjoyed the meal and she poured him a drink. Curt excused himself, “Well, I got to be going.”

Barb approached him several days later, wanting to know when he could leave for Spain. “Two weeks,” he guessed. “As soon as I can get a passport.”

He arrived in Seville. A driver, standing patiently with a Herrmann name card, greeted him. Michel, a Belgian with a repertoire of six languages, was the local Hearst administrator, and, for today, a chauffeur. They headed for the farm of 2,000 acres, littered with olive trees, located 15 miles northwest of Seville in the Sierra Morena foothills village of Gerena. The Hearst property was called Finca la Caprichosa (The Whimsical Farm).

Driving up to the main house was a flashback of the initial image of Roth Hall in Hyde Park. Joanne’s house was huge. A tired Curt unpacked in a small apartment by the courtyard. An attractive group of uniformed girls stopped by to welcome him. Curt thought, “All right.”

He sat down with Joanne, sharing some snacks and a couple of beers. She gave him an overview of his responsibilities and told him to order some chef garb. He, too, would work in uniform. Expensive sets of French chef wear arrived at his flat. The original eight-month plan turned into nearly three years and Joanne nicknamed him Curro (flashy; Frank).

“It was a total drug,” Curt explained. “We traveled all over the world, I had a car and an apartment, nothing was at my expense, except for beer and cigarettes. I made good money.” He was pleased to share some of his earnings with the Tulsa shop, if it were needed. “No big deal,” he added. Hearst did not need a subsidy.

Local produce, cheeses, Spanish hams and farm-raised poultry made this a cooking paradise. Sometimes it got a little weird. The second Thanksgiving of Curt’s tour of duty had fried turkey on Joanne’s menu. This would be a new experience for the private chef. He followed two hired hands, Manolo and José, into the horse barn.

They stopped at one of the stalls. Two bottles of brandy and a funnel accompanied the two turkeys from a neighboring farm. Curt remembered thinking, “This is going to be Napoleon all the way.” The tradition of preparing the toms for dinner began. Manolo approached a turkey and slung a leg over its back, grabbing it by the neck. Curt placed the funnel in the gobbler and started pouring the brandy. The turkey drank until the bottle was half gone. Although still conscious, it no longer squawked.

Within half an hour, the staggering turkey consumed the rest of the bottle before Manolo ended it. “I will say,” Curt reported, “That turkey was so tender; he’d been so relaxed.” There was no hint of the brandy in the servings. It was an unusual day, but he grew to expect unusual.

Joanne would prove to be a challenging taskmaster with food requests 24/7. Leaving his eccentric patron behind, Curt returned to Curt & Marj’s.

As with many businesses, their enterprise morphed. For several years, the facility changed from a deli and carry-out to a restaurant with white tablecloths. By the time Curt returned, it was a full-on catering business, having eliminated the headaches of a restaurant.

**

A year and a half later, Curt’s friend Philippe Garmy helped chef a wine dinner with culinary great Stephen Giles. Giles owned the Sage restaurant in California. He used to work for Chef Michel Roux in London, who ran the three-Michelin star Le Gavroche (which means an urchin or street child in Paris). Garmy suggested Curt cook for Roux. Curt said, “Hey, Marj, what do you think?” Again, she encouraged him to take a culinary chance.

Giles never met Curt, but connected him with Roux’s personal secretary, Marion Aputa. She emailed back that he could start at Le Gavroche on such-and-such a date. The contract would be for one year—if he could make it—and there were stipulations. He had to pay his airfare to London. They would put him in the Lords Hotel (Bayswater) near Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, but if Curt did not survive three months in the kitchen, he would be responsible for paying his lodging costs.

Several weeks later, a package arrived from Roux. It contained his visa, pamphlets, maps ... all he needed to enter the country and become familiar with his new environment. He had been fast-tracked through the system by the Roux influence.

Curt bought new knives and headed for Heathrow Airport. He took the Tube on the Blue Line. His stop was Holland Park Station but he missed it. He ended up in Soho, tired, lugging a huge suitcase up the subway stairs. The heavy case and the heave-ho up the steps took its toll, the handle ripped off. Finding his way, Curt rested for what he knew would be a very serious kitchen.

Le Gavroche was started in 1967 by Albert and Michel Roux. At the time of Curt’s arrival, Albert’s son Michel ran the Michelin-starred establishment, which features a “modern French” style—classical French influenced by Mediterranean and Asian flavors and ingredients, creating lighter fare.

Curt started as a demi chef de partie (executive chef’s assistant) at the amuse bouche and salad station, along with several other newbies—cleaning lettuces, making vinaigrettes. His position was a satellite for Garde Manger (a person in charge of classical preparations like pâtés, terrines and elaborate aspics) and the starters stations.

If a new chef mastered the station quickly, they were moved to another. Curt moved on in a month. Chef de Cuisine Nico, a Frenchman, yelled out, “Yank, move to the vegetable and starch station.” Curt had been promoted. He had survived his baptism, yet struggled with the accents of his global comrades.

The kitchen was an ethnic melting pot of 24 cooks that provided Michelin-level product for the 24 waitstaff to sell and serve and two Master Sommeliers to pair. Orders barked out might have a Korean accent added to broken English that did not communicate well. The solution for Curt became a system of hand signals. No problem. He had bigger challenges: his current station. It was hard.

Curt arrived at 7:30am to prep, then lunch service, followed by a complete breakdown of the kitchen that included scrubbing all the flat tops, up in the hood, down on the floor. Some would go out to the pub for a few beers before returning to re-prep for the evening onslaught, hustle through dinner service and leave the 62-seat restaurant around midnight. Taxi rides were $25 from Lords to Gavroche. Curt walked: “Those were long days.”

After several months, it started to click. “As soon as I got to know what I was doing, guess what,” the talented chef recalled. “Mr. Yank,” Nico yelled out, “You’re on the fish station.” But he was moving up, while others languished.

It seemed he was doing something right, but now, at a new station, he had to start over. He was clueless. Yet to not produce, even the first day, was not acceptable. If you were slow, plating was interrupted and tempers flared. Ben, a Brit, was then on the garnish line and he could not get it. Nico was the expediter, who gave his blessing to each plate as it went out for the 100 covers with as many of 10 courses each.

Yelling at Ben, the irate Nico headed for the bewildered cook during the middle of lunch service, slapped him upside the head, knocking him into the rack of metal pans and running him out of the kitchen, giving him a few more slaps. “Mr. Yank,” the fuming chef ranted, “you’re on garnish.” That was how it went. They didn’t fool around. The need to send Curt back to garnish for two months, kept him from being elevated to the meat station, the only station he didn’t work before his year was up. Curt raised an imaginary glass, “Thanks, Ben. Cheers, mate.”

Curt’s last station at Le Gavroche, before the Christmas–New Year’s break, when the restaurant heaved a sigh of relief and his contract ended, was pastry. On his final day, Curt got the customary handshake from Nico, the last pay envelope. He had seen the routine when others left. Dinner service had ended and Michel Roux is, generally, out the door for home. Curt had one, last pastry order, a three-top. Curt noticed Roux enter the kitchen and sit on the meat station, talking with Nico. Unusual.

Roux approached Curt. “Here’s your envelope, Mr. Yank. Good work.” The Michelin chef also handed the Chicagoan the elaborate Le Gavroche base plate and quietly left. This was not the usual departure gift. Curt was touched; still is.

Le Gavroche was a good teacher. Curt had learned to be intensely focused on the food in front of him. He screened out all the kitchen noises, except those he needed to accomplish his task. Everything he did was about the food. He had become intense about detail, perfection, timeliness. He had given his best, every moment. Now it was over and he felt a big weight leave his psyche. He headed for his favorite speakeasy on Bayswater and drank big steins of beer. He had a couple of weeks to kill—no pressures, no immediate place to be.

Curt headed back to Curt & Marj’s as a seasoned chef who had integrated the rigors of re-proving his abilities each time he was advanced to a new station, enjoyed the availability of unusual products and managed the intensity of working for perfection at a three-star Michelin restaurant. “Curt returned with a different eye for detail and quality that few would have appreciated,” Marj said, adding, “I guess that is why there are so few three-star restaurants in the world.”

For two years more years, the duo worked side by side. The mainspring of the shop wound down by 2005. Marj married Bill Tallen, lived with him in Ft. Smith, Arkansas, and became pregnant. During this transition period, Wild Oats wanted to expand into their space. It was perfect timing. Curt sold the equipment, piece by piece. With the space nearly empty, Barb Hanford rolled in:

“Hey, Curt. You want to go back to Spain?”

“Sure, why not,” Curt shrugged.

Curro headed back to Spain and Joanne for a second three-year experience. But the working environment, eventually, took its toll. An embattled Curro retreated to Chicago.

After three months in Chicago, while looking after the health of a relative, longtime associate Jason Hunt called him, asking him to help start up a new Tulsa venue, the White Owl pub and restaurant on 15th Street. With Curt’s guiding hand in the kitchen, the enterprise became a focal point amongst the Cherry Street crowd. Looking for a teaching environment, Curt headed for the confines of the new Culinary Institute of Platt College in Tulsa.

The program was designed and led by Chef Jeff Howard, who built up the respected curriculum and managed the entire operation. Howard was the glue. “Curt came into the school to do a charcuterie demonstration, meat butchery and all that involves” Howard recalled. “The students were mesmerized.” Over the years, he realized that Curt’s personality has always been why people are so drawn to him. “He is all right there in front of you; there is nothing hidden, such an honest person,” Howard added. And then there is his talent.

From an early age in Chicago, Curt began to develop his palate and a sense of what he could do with food that excited people and was interesting to him. “He has always done really cool food,” emphasized Howard. “It was a great opportunity for us to bring him in to teach.” With time, the boss grew to know his garde manger even better.

For the first three years at Platt, Curt led the garde manger during the day and filled in classes like international and such in the evening; double shifts every day. The last four years found him adding lunch and dinner service to his plate, as well as continuing to fill in for some of the classes. The serious students got his full attention.

Curt admonished his students to establish their own food identity. While it is good to know, what others have done or are doing, don’t try to copy them, he said. Cook what you like and like-minded people will find you. Keep it simple, Curt continued his lecture: “You don’t need 20 things on the plate. No more than three or four on a plate. Shoot, one thing. But do it well.”

Chef Herrmann also taught respect for the cooking profession of the past. He did not allow big bandanas in the kitchen, nor Bermuda shorts. Proper chef regalia was expected and honored. Curt was firm on this point, “Respect tradition—I used to nail that into the student’s head. When respect for the kitchen goes away, it won’t come back. That’s what I taught the students.” Curt laughed, “So maybe I was a bad dad.”

Curt strongly advocated proper technique and good knife skills to his protégés. He emphasized they understand the ratio of the ingredients in a recipe and how those elements interact—why you, as the cook, are doing what you are doing with the ingredients. “It’s always been like that. Europe developed that standard years ago. Old World, you know,” he sat back and smiled.

To Howard, Curt may have been born 60 years too late in some respects. “He doesn’t want to mess with the technology, but prefers grinding all the meats by hand, turning the crank; whisk rather than use the mixer. Curt prefers old classical music and war documentaries. He is unabashedly Old World, old school in everything he does—loves to be in the kitchen,” said Howard. As do others on the Platt Culinary staff.

Chef Rex Morris played an important role for Curt during his Platt years. “Rex is one of the nicest, wisest men I know,” Curt said. During Morris’s visits to see Curt, the two chatted about culinary, life in general and the activities at Platt since Curt and Howard left.

Reflecting on his seven-year teaching career, Curt offered, “I would come home at night and pull up to the computer, thinking about what I had said in class that day and what we needed to do tomorrow. I typed up the mise en place (organizing foodstuffs) for the next day—you know, a casual planning period.” It had always been about the food, always the passion for the food.

**

A frequent visitor, a journalist, knocked on the outer screen door of Curt’s New York–style apartment. “The door’s open,” he yelled, “Watch the step down.” Always the same greeting. Settling in with a couple of cold brews, Curt mentioned that he had just spoken with Marj.

Marj lives in rural Wyoming, between the entrance to Yellowstone Park and the city of Cody (population 10,000), which honors the life and legacy of Buffalo Bill Cody and features a not-so-great sushi restaurant and a new Walmart. She and Bill are raising their 12-year-old daughter, Ida. Curt and Marj are still close. Bill’s cool with that. He is aware they met at Culinary, had various business and personal adventures and cherish their friends-forever relationship.

During a phone conversation, Marj emphasized that Curt is totally genuine, has the kindest, most humble heart. “He may try to hide it, but it is his natural way,” she said. And his entire life has revolved around food. Marj recalls that he would think about food before he went to bed and when he awoke. The visitor and Curt swapped fond stories about Marj, then the chatter turned more personal.

**

Curt Herrmann was in failing health. Resigned to his fate, he took a sip of water and told this part of his story. His future was undeniable; doctors had informed him. A favorite chef to thousands of patrons and students knew his time behind a hot stove was over. Medical professionals advised him to tie up any loose ends. With the help of Marj, he has it all under control.

Asked what he might choose to cook as a memorable meal, after a pensive pause, Chef Herrmann responded, “What do I have a taste for? That’s the biggest thing—gonna be foie in there somewhere, gonna be truffles in there somewhere, gonna be caviar in there somewhere. It used to matter what ingredients would go best with what product. Now, there is not as much thought,” he said. “It’s not as important anymore. Right now, I have a taste for beef tongue and some mustard; I’m happy.”

Sitting in his recliner in an apartment of a historic Tulsa building, filled with chef memorabilia—china plates from prestigious food and wine organizations, framed newspaper articles and the like—Curt shared, “Sometimes you need to come to your person and realize you will never do what you once did. Now, it’s time to take off the chef jacket and read the paper. And I am OK with that.”

Marco Pierre White, a hard-core English chef, threw his Michelin stars to the wind, deciding it was not worth all the hardcore hubbub. He gave them all back. It was time for White to exit the intensity of the food scene, time to turn the page. Curt identifies with that. You give it all back.

“I am thankful for all the situations, as they unfolded over the years, but now they are gone,” Curt said. “Wouldn’t change a thing. Nah. Nothing.”

Curt Albert Herrmann passed quietly in his recliner on Wednesday, July 5, 2017.