Another Confusing Story About Belgian Ale

Pete said, “We’ll meet on the Grand Place.”

The center of old Brussels, UNESCO crown jewel and historic food market and revolutionary hitching post. He’d finish up some work and meet me later that evening.

“There’s a place around the corner that we love,” Pete said, grinning very Englishy. “A plate of moules-frites and a couple of Belgian ales and I’m in heaven.”

Pete favored the Wallonian beers and may still, Wallonia being the lower, French-speaking half of Belgium. I didn’t speak French and certainly not the Brussels version of it. I went to a café and read the London Observer, which was publishing its first reports from Kandahar. It was that generally happy-crazy time, between Thanksgiving and Christmas.

The evening turned to night in the Grand Place. The shops closed, the restaurants filled. I walked the square for a solid two hours. No Pete. Repeat: No Pete.

I ended up dying, cold and lost, and finding heaven on my own in one of the old brasseries on the Place. A pile of mussels and fries and two Chimay bleus later and I was sanctified, with enough mettle to attempt the many digits of the phone card in my pocket. Pete answered, guided me to a tavern on the Rue du Marché aux Herbes, where I ordered a Leffe Brune and waited. Brune is OK but gentlemen prefer Blondes. An hour later, Pete pulled up. In the car, he asked where I’d eaten dinner and I could only point.

“Oh, that’s too bad,” he said, telling me his place was so close I probably smelled the aromas. “You were right there.”

Pete navigated the many and wondrous roundabouts of Brussels, mindful of the occasional cyclist. “Belgians are crazy about bicycles,” he said, as one zipped into our headlights and then out. When we got back to Watermael-Boitsfort, I was so strung out that I cracked an ale and watched MTV. I can’t remember the label on the bottle. There are only about a thousand it could have been.

I confided to a friend that I’d undertaken the dubious task of writing about Belgian ale. He looked at me suspiciously and shook his head, “Why?”

“Because everybody’s into Belgians now,” I said to him. “No they’re not,” he said back. “They’re into IPAs and Imperial Stouts.”

In fact, they’re into cheap lager, same as always. The American craft brewing market has been chipping away at the Buds and Millers and, in 2014 data, finally grabbed a double-digit (11%) volume share of the marketplace. In this new market, “Belgian” carries a kind of weight. Though, even in Belgium, it’s the pedestrian Jupiler and the more heeled Stella Artois that dominate. Those aren’t the Belgians I mean when I say “Belgians.”

“The great beers of Belgium are not its lagers,” said Michael Jackson, the legendary “Beer Hunter.” “Its native brews are in other styles, and they offer an extraordinary variety, some so different from more conventional brews that at the initial encounter they are scarcely recognizable as beers. Yet they represent some of the oldest traditions of brewing in the Western world.”

“Anno 1240,” proclaims the label on a Leffe Blonde. Think of all that’s changed, except Leffe, in all that time! Leffe is about as common a Belgian pale as there is, and yet it captures remarkably the Belgian … thing that everybody who craves it raves about. I know only what my mouth tells my mind. I could say it’s all about yeasts and candy sugars and secondary fermentation but you’d stop reading. Anyway, it’s really about tradition and style, trial and error over eons. Brewers talk of yeasts with a reverence usually reserved for saints and sports teams. Discuss the fruitiness of esters and the flocculation of fermentation long enough and you could hold court over Belgian ale the way you might over NFL combine results.

I can’t explain it (or maybe just won’t) but it’s why I like New Belgium’s Abbey (a dubbel, and its Trippel, a tripel) but not its Fat Tire, classified as an amber ale and packing none of the fruity punch of the dubbel. Talking phenols and esters, spicy and fruity (versus the actual fruit beers, called lambics), you can get into the weeds pretty quickly. Like American Solera’s own review of its award-winning Foeder Cerise, classified by the Beer Advocate an American Wild Ale, but a lambic at heart:

“A sour golden ale brewed with a mix of brettanomyces and several different souring cultures. We then age it for six months on top of Montmorency cherries. The flavors produced are sour cherry and cinnamon with a touch of brett funk. This batch comes from our 30bbl Italian oak foeders.”

Of course, you can just drink up the funk. My first foray into Belgians, like a lot of ale drinkers, was Chimay. We can probably thank Father Theodore (“God’s gift,” in the native Greek), brewmaster at Chimay’s Scourmont Abbey, a Romanesque villa with a tree-lined lane and housed by various monks of all nations and tribes, some wearing Nike trainers as they file in for morning chants. Out back, over the brick wall, lies the cemetery of monk men and, in the air, the aromas of bread baking.

Rik Kat used to run, and may still, a café in France called Le Lezard Bleu. Rik turned me onto all kinds of Belgian goodies at his little bar above the River Orb.

“Rik, why do you have so many Belgian ales?” I asked him one day over a bottle of Delirium Tremens.

His tiny bar had only two or three taps and would seat not many more. Behind the bar, he stocked a good two dozen Belgians and counting. Dutchman Rik Kat, who met his French wife in London, moved to southern France to open a bar featuring Belgian ales. “Because they are the best beers in the world,” he said.

When Rik found out we were heading to Germany to meet a friend, he told me to stop in Achouffe and buy all the La Achouffe we could carry. “Not Mc Chouffe,” he was adamant. “The golden.” La Chouffe is classified a Belgian Strong Golden, an Ardense Tripel elsewhere. “Welcome to the Valley of the Fairies,” a sign at the tasting room greets you. We loaded down the trunk and made for France, getting stopped twice by border patrols looking for smugglers.

But not our kind.

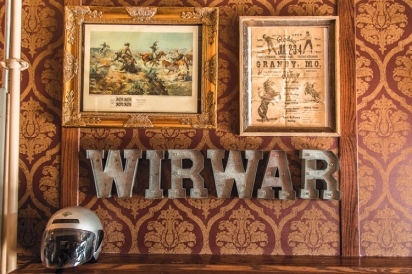

Near Antwerp, in Flemish Belgium, is a town called Turnhout, head office to Cartamundi, largest manufacturer of playing cards in the world. It’s also home to Wirwar, a kind of Low Countries honkytonk.

In the Boxyard, Wirwar Tulsa packages “Belgian street food, beer and hillbilly music,” not unlike its Belgian namesake. JD McPherson, Broken Arrow public school teacher turned retro rocker, has been in Nashville for the last two years. When he found Wirwar Turnhout on his travels, the combination of country music, good beer and cheap food struck a chord.

“I wanted to open something much larger, with the same theme, on down the road,” he said. Then a buddy offered to back him in the smaller, Boxyard version. A Belgian dive locked in a shipping container. Oh, the possibilities.

“Come on, today is a good day,” McPherson told me. “Brewery Ommegang Game of Thrones tap takeover is today, and we just added a chicken and waffles option.”

It was Bastille Day, a fine day for an “Iron Throne” — a 6.5% Belgian Pale, sayeth the BeerAdvocate. Ommegang, out of Cooperstown, New York, is now owned by Duvel, one of the great Belgian Goldens. I always get it confused with Orval Pale, one of the 11 Trappist ales (see sidebar). A good way to the tell the difference is the bottle: Duvel’s bulges in the neck, like a bad water balloon. Wirwar serves them both.

They also serve a mean poutine, a pile of fries lathered in carbonnade (beef stew) and, um, garnished with fried cheese curd. Wirwar doesn’t take itself too seriously, in spite of all the hard-to-say menu items. It’s got the battered wood floor of any old dive, and fleurs-de-lis wallpaper reminiscent of some Old West saloon. There are movie posters for classic westerns: Jimmy Stewart turning Apache in La Fleche brisee (Broken Arrow) and Spencer Gordon Bennet’s Le glas du hors-la-loi (Requiem for a Gunfighter). I sidled up to the brass rail and ordered a Westmalle Tripel, an act of consumption almost unimaginable even five years ago. Chase Kline, who manages the place, had been living in Chicago. He hightailed it home to run Wirwar. “Holy shit,” he said, “everyone’s doing stuff now!”

In time, Kline wants to stock all the Trappistes, but he also keeps cans of PBR and Good Ass cold and front and center. “Got to have the crowd pleasers,” he said. In fact, It’s a Maes Pils neon that hangs over the Wirwar in Turnhout, in Flemish Belgium, on the Dutch border. Corsendonk is a stone’s throw, home to a legendary brown ale.

“Has a very distinctive bouquet: yeasty, fruity and slightly smoky,” said Michael Jackson.

“Taste is flat cola, dandelion and burdock,” reads a chat room comment at beeradvocate.com. Burdock is a plant root sometimes used as a bittering agent. I had to look that one up.

When the Game of Thrones tap finally got cold, I drank a Bend the Knee, a Golden Ale, 9% ABV, pleasing a crowd of one.

Abbey v. Trappist … talk a-monks yourselves

Simply put, an abbey is a only a name but a Trappist is a classification. You have to be a Trappist monastery to put “Trappist” on your label. Any heathen can call its ale an “abbey.”

Chimay, a Trappist monastery, used to make beer only for itself, a 4.8% Belgian pale labeled Doree. One time, it was the only ale made on premises, hence the sometimes-name “singel.” Chimay was the first Belgian monk beer to go global, marketing three styles: a dubbel (the red-label Première), a tripel (white Cinq Cents) and a Belgian Strong Dark (blue Grande Réserve). Some would call the latter a “quadrupel,” or “quad,” arguably because it’s stronger than the tripel but, more obviously, because it’s fourth in the lineup.

Quadrupel is not a style in the 93-page style guide of the Beer Judge Certification Program, which—for those scoring at home—does denote a “Belgian Strong Dark.” The BeerAdvocate, however, does acknowledge the quad.

Whatever. I’m only doing this bit for Steven, because I said I would.

“Get to the bottom of this dubbel, tripel, quad thing, will you?” Steven all but begged me.

Steven, I’m trying.

“Can someone offer a quick explanation of Dubbel, Tripel,

Quad, Abbey?” somebody typed in at the BeerAdvocate. There is certainly no quick explanation and probably no convincing one, either.

It would be tempting to say it’s all about octane, but alcoholic heft appears to be more a self-fulfilling prophecy than a pre-programmed result. Chimay’s red is 7% alcohol, its white is 8 and its blue 9, but the math isn’t always that tidy. For instance, the St. Bernardus Prior 8, a dubbel, is 8%, same as its tripel. (It’s Abbot 12, a quad, is 10.) Rochefort, another Trappist, makes a 9.2 Belgian Strong Dark and an 11.3 quad. It also makes a 7.5% dubbel labeled Rochefort 6. Drunk yet? The Belgian nomenclature aligns poetically with that of baseball, so let’s try this:

Singel: Slap hitters. You can make a career out of it but your Topps card isn’t likely to appreciate over time. Somebody has to start the rally. Dubbel: A bit more pop in your bat—a lot more, actually. Singels knock in runs but so do dubbels, while also putting themselves into scoring position. Dubbels find the gaps.

Tripel: A speedier version of the dubbel, with longer legs.

Quadrupel: The problem with the long ball is, if you sit around waiting for one, you miss the action. Baseball is played largely on the basepaths, not in the over the fences. A dubbel with men on base is more dangerous than a solo homer.

Batter up!